Mom Gossip: Alessandra by Jacqueline

"I couldn’t give you the Amalfi Coast, but I could give you Waldorf."

Welcome back to Mom Gossip, a column celebrating the women who shape us. So far, we’ve explored foot baths, astral travel, and Celtic Druid traditions. If you’d like to interview a mother in your life, get in touch here.

Today, we have a conversation between Jacqueline Morassutti and her mother, Alessandra. Jacqueline is a writer and regenerative farmer living on Vancouver Island. She was a guest on the newsletter last November.

Below, Alessandra shares her experiences studying homeopathy with George Vithoulkas, how motherhood became her gateway into alternative health, and the unexpected freedom that comes from being headstrong.

I’ll let Jacqueline take it from here…

Mom Gossip: Alessandra by Jacqueline

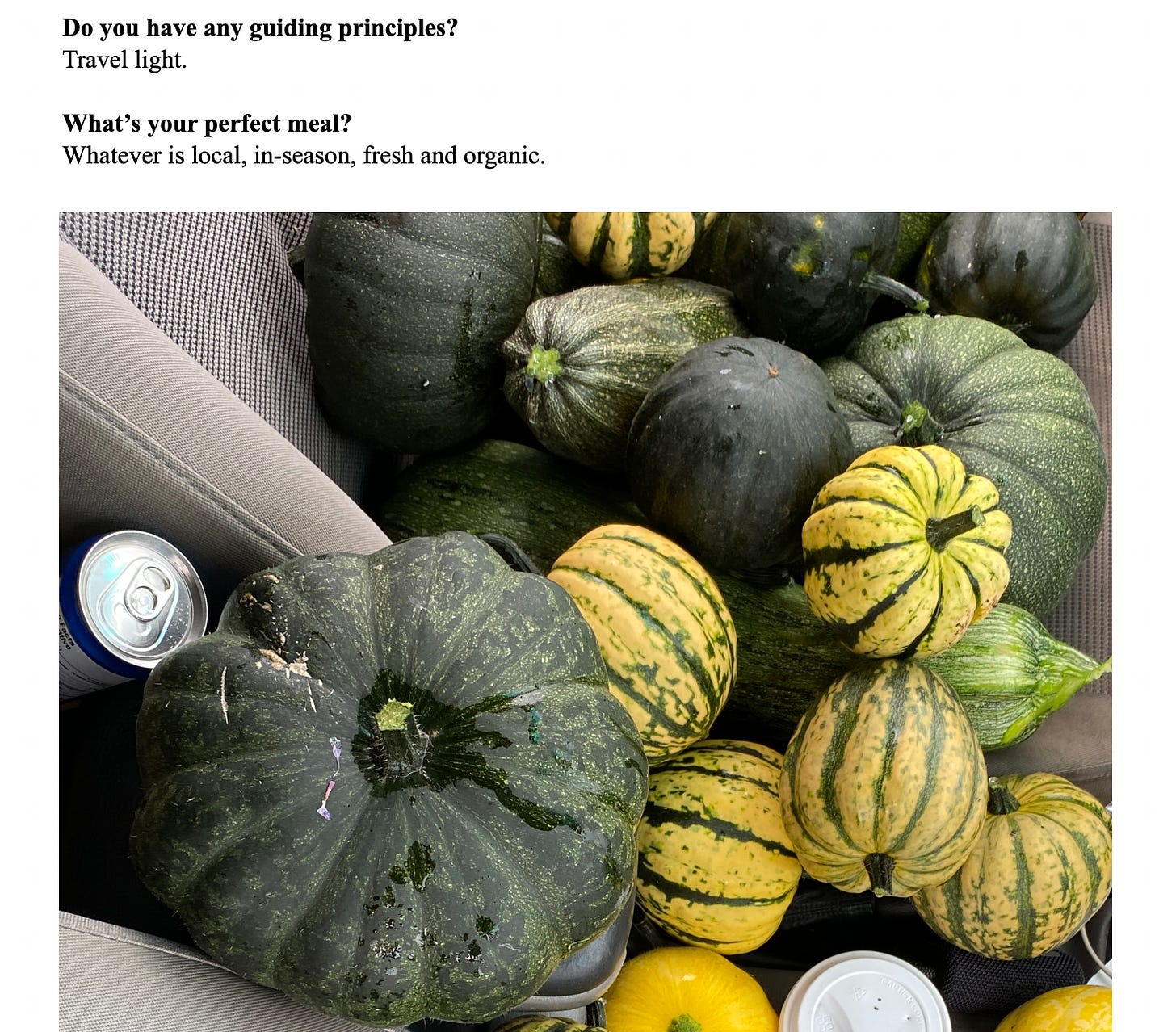

This interview is the result of a series of phone calls, voice memos for clarification, and a winding tour of family history. Growing up, I’d heard stories about my mum’s childhood between Naples and Ischia, her unruly adolescence in Montréal, and her entrance into motherhood in Toronto. She made it clear that there were no absolutes around health and wellness when she was young. There were cultural instincts that you were either aligned with or not. That was the extent of her concept of wellbeing.

When we were talking about doing this, you were quick to say that you didn’t set out to pursue any alternative health or wellbeing practices; you were just starting a family.

I was so green to motherhood, but I had a good instinct, and I think it was because of my upbringing — to keep it as natural as possible. I couldn’t give you the Amalfi Coast, but I could give you Waldorf. That just felt so right to me, but it made no sense to anyone else. I think there was this sense of independence: right or wrong, I was going to do it my way. I never felt the pressures of, you’re not going to belong, they’re going to call you names — that’s okay, I’ve been called “crazy” all my life. I’m not afraid of that, and that’s a gift of being an immigrant. I was able to do my own thing without being concerned about the consequences.

In that way, I’ve always had a hard-headedness. There’s a freedom in that that’s quite lovely.

Becoming a mother opened this door for me and it really allowed a lot of knowledge and new information to come in that put me ahead of the times. It really was a gift. It opened me up to all alternative medicine — almost to a fault, because I’ll try everything just to see what else is out there.

What did health and wellbeing look like during your earlier years?

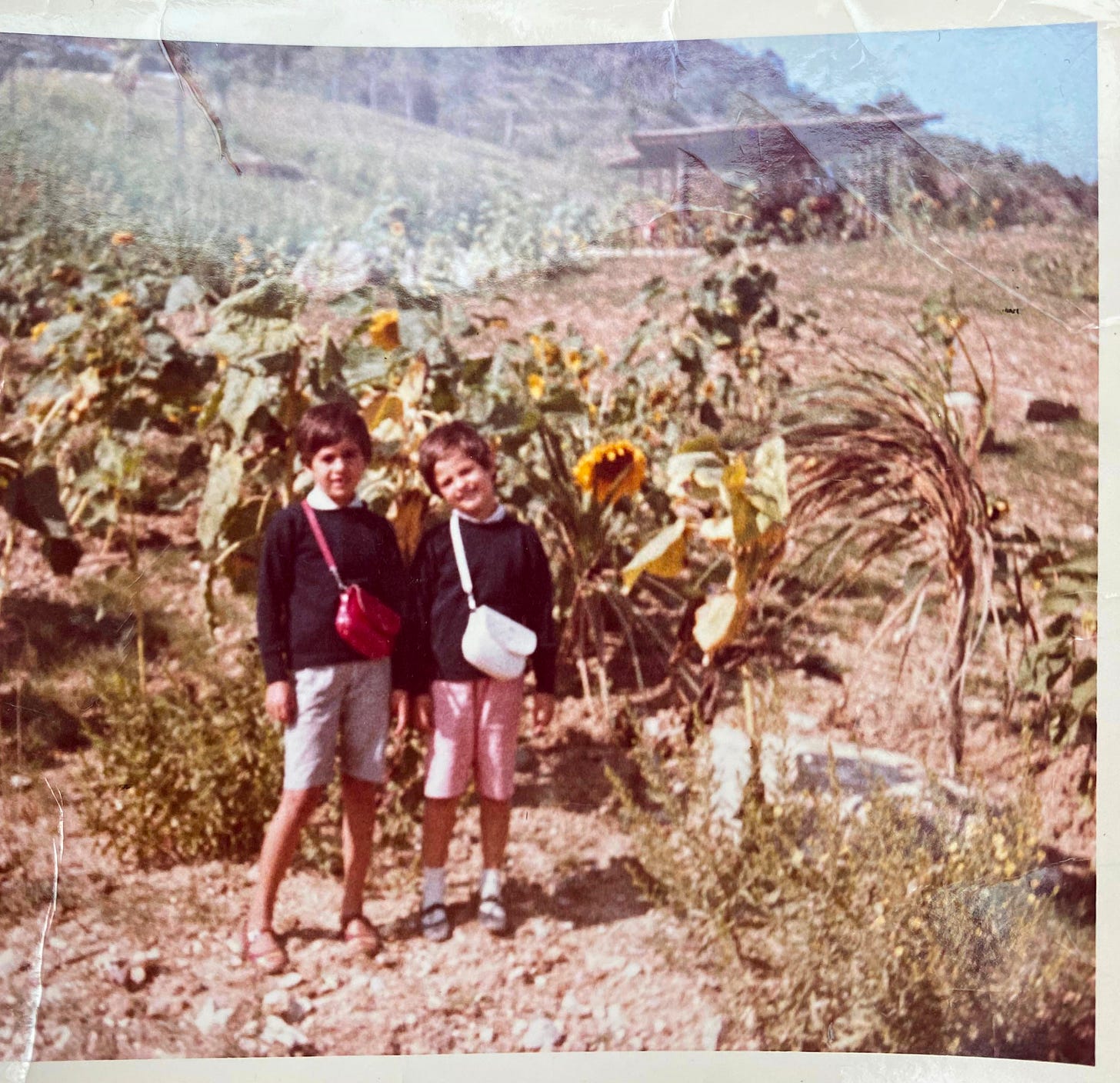

I’m going to start with a little story that I’ve shared with a couple of people. So, we’re talking 30+ years ago, I never would have said this at the time, but I think we were at a sort of Golden Age of the planet, of wellbeing. If you had a little bit of means you were able to buy decent food. Also, because I grew up with an Italian culture of food, we tended to eat fresh things. We just didn’t eat packaged things. There wasn’t anything that I had to relearn or do, you know.

You’re going to buy top food, but you’re going to have less of it. That’s the culture.

What did that look like on a day-to-day basis?

Well, if I was going to get a nice steak from the butcher, I would and I would get some vegetables to go with it. It wasn’t fancy, but it was good food, which was part of my culture. We were always going to buy good food. It wasn’t like we had to watch for “organic” and all this, no, that came after for me. I think when I was pregnant that started, because I was out in Vancouver, and they had more organics. Being pregnant did make me more aware, but it was also the environment, because when I came back to Toronto organic food was harder to find. At the time there was only The Big Carrot. Then, even though organic food was priced a little bit higher, it was part of the Italian culture. You’re just not going to buy shitty food. You’re going to buy top food, but you’re going to have less of it. That’s the culture.

It’s funny, I’ve never heard it put that succinctly but you’re right. That reminds me that even when I was working for various Italian restaurants in Toronto there was also a strong emphasis on having the Materia Prima, the best raw materials.

Exactly. You’re not going to cheap[en] the meat. You’re going to get good quality but you’re going to get smaller portions. That’s the way it is.

Something else I remember is that when we were little, if we had a cold, my dad would warm up the cognac, give it to us to drink then tell us to go straight bed where we’d just sweat it out. Do you know those espresso machines, where they would steam the milk? I remember once when we were in Ischia, and I got quite sick, this guy steamed the cognac in the machine. I drank it as it was cooling. That night, I barely made it to my bed. I was out. I woke up the next morning. I had been drenched, sweating all night, and in the morning, it was all gone.

Another experience I’ll never forget, I came home, and my wisdom teeth were causing me a lot of pain. My dad gave me two shots, probably four ounces of cognac, didn’t bother to warm it up, told me to drink it straight — and it’s not nice to drink when you’re fourteen, fifteen, okay? — and then he goes: “go to bed.” That was the pain killer, brandy.

Some elements of your story are very relatable, and others elements might inspire courage in people.

You know, I never really thought of it as courage. I really think that being immigrants, where we saw struggles in the home and we saw father who had some difficulties, and that we overcame that — we got ourselves degrees and we were able to get out of the house… those successes empower you, even though they were small.

I’ve always had a hard-headedness. There’s a freedom in that that’s quite lovely.

Today is a different world. It felt more simple, more organic, and because we were immigrants without being held by too many rules and regulations of families; we were a little more free with how we could move. I wasn’t going to get my uncle or my aunt calling me because I’m now defaming the family. I got a little bit from dad, but I was really free. It was lonely not to have the big family entourage, but it really allowed for a lot of freedom to really be the rudder for your life. You [could] imagine it in your own way without any influences.

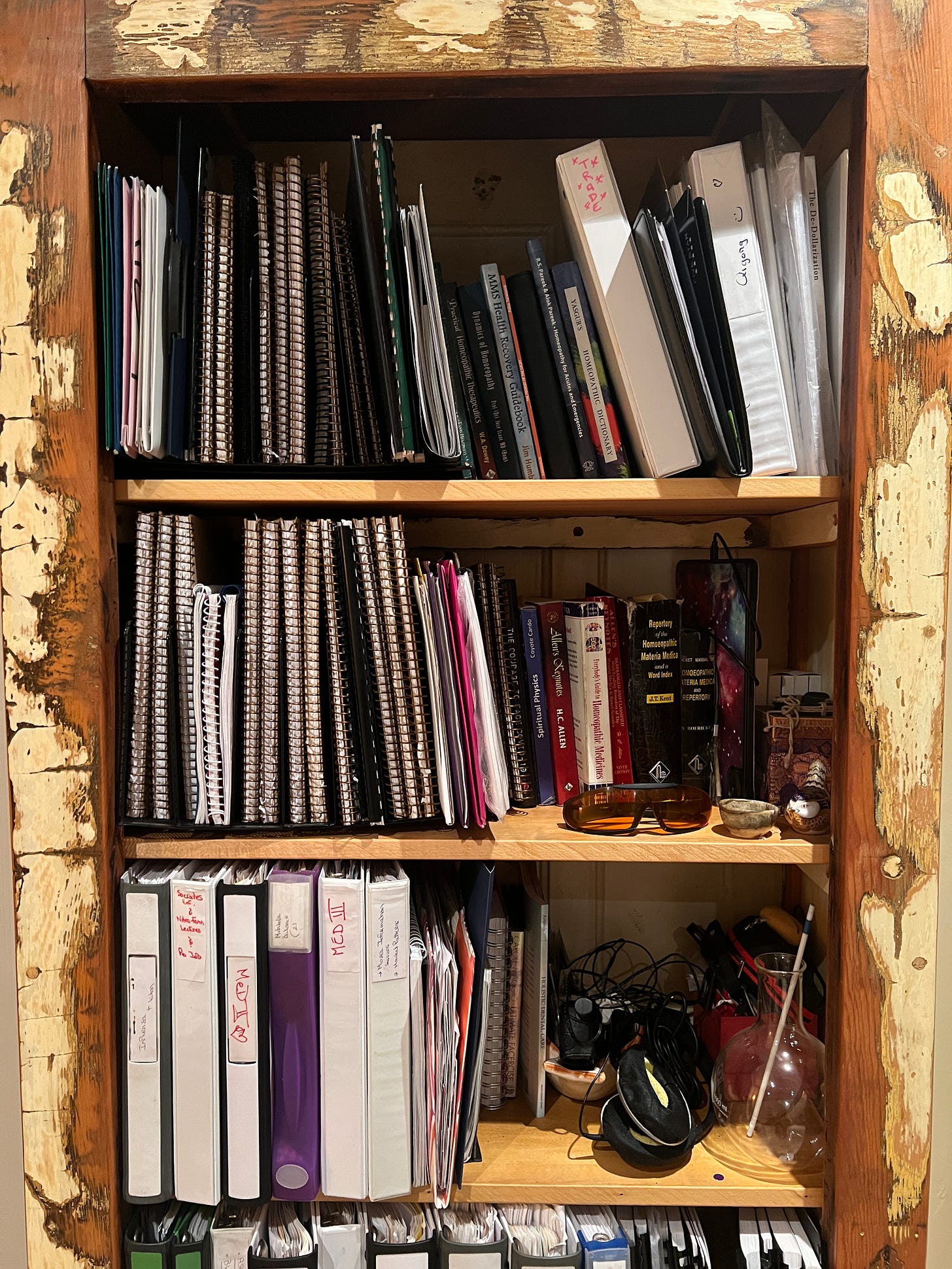

My understanding is that there are a few different schools of homeopathy, and you studied from a couple of them. Do you remember what drew you to one versus another?

The main teacher was George Vithoulkas in Greece. He has a very classical approach: one person has one remedy at a time. We learned about taking full cases, whereas other schools of homeopathy focus on whichever symptom is present. Vithoulkas’s approach is perfect for laying the foundation, understanding the key essences of the remedies and how they would match a person’s constitution. He was trying to teach the big picture about how the body heals; if you give the body the right stimulus, it can take you back to health. That was his big teaching, along with the keynotes of the remedies. You don’t give too much, then you wait, and the body will give you its response.

He was really trying to stay very pure to the teachings of Samuel Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy — which is a beautiful thing but not always applicable in clinical settings. Vithoulkas’s style can take a long time, and it can be difficult to figure out. If you have a client on the phone and their child is coughing its guts out and you don’t have time to take their full case, it gets hard to find the right remedy.

You don’t give too much, then you wait, and the body will give you its response.

So, then I sought out more clinical approaches to homeopathy. Friends of mine were working with Dr. Jose Issac in Thiruvananthapuram, India. Dr. Jose was also classical, but more for the hospital setting — you know, when you have a patient coming in and they can’t talk, how do you assess them?

In the hospital setting, the doctors are trained to find the remedy for the acute condition by visual cues or by one or two symptoms.

Can you give me an example of what sort of visual cues you would use?

For example, if someone comes in with water or food poisoning, the first remedy you think of is Arsencium 30ch, or if a child that comes in with asthma and is always hot you would give Arsenicum Iodatum 30ch, or someone has a high fever and flushed face you would give Belladonna 30ch. So, with very little information you can give something and offer a person a lot of relief, which is amazing. You can repeat more often if a patient is in an acute phase of the condition, because they need more support and they tend to burn through the remedy quickly.

I remember hearing you and other students referring to “the levels of health” while discussing various case studies. Where did that concept fit into these different schools?

Right, so according to George, there are four levels of health.

Level One would be somebody who is very healthy. When they get an acute symptom, they get a very high fever. They’re in and out of the acute phase with 24-48 hours.

In Level Two, you’re starting to see more acute symptoms more often. You’ll see more fevers, colds, stomachs, earaches happening on a regular basis — maybe three, four, five times a year — whereas somebody in the first level of health would get that once every two years, and it’s progressive, you know. You don’t jump from Level One to Level Two, but if you’re getting colds every 2-3 months, then you’re getting close to leaving the second level of health.

Level One and Two are good health, Level Three and Four are on the other side. When you stop getting high fevers or issues that are on the skin, you’re getting into chronic conditions because the inflammation is now not out in the open for the body to deal with. Now the inflammation is under the surface because you’ve stopped the first level of defense that the body can show you and you’re going to deal with more chronic conditions. I don’t want to butcher this, but that was revolutionary. We were all sitting in class when George told us this and looking at each other like, Do you get high fevers? I don’t get high fevers anymore. In a class of 150 students, we realized that half of us were not getting high fevers anymore. It turned everything we knew about health upside down. I think now there’s more of an acceptance, in some circles, to allow fevers to run, but at the time, 20-30 years ago, it was revolutionary.

The doors started to open, and I saw that there were other ways to heal.

What he observed was that the first two levels are in the best health, which would help you when it came to prescriptions because you would only need one or two remedies, and they would be totally fine. Even if they were in a degenerative condition, you could give them one remedy and they would be cured because the response of the body was so strong that it was able to get rid of whatever it was that was ailing them with a lot more power, a lot more vitality. Once you’re in the Level Three you’re going to need more remedies, you’re going to need more repetition and you’re going to take longer to get through it, you’re going to have to change more things in your lifestyle.

George came to this understanding because he had many doctors in Athens that were following his prescription methods, and he observed through his team that helped people go from disease states back to health. His observations gave him insights into how people heal, which happens when you’re treating so many people. He started to realize that there was an intelligence in the body that as the body starts to heal, it goes through certain stages. That’s how he ended up distilling this concept of the Levels of Health.

Homeopathy was really a gift, to have a medicine that really can relieve you of discomfort right away (if it’s the right remedy). There’s nothing else like it. The doors started to open, and I saw that there were other ways to heal. Which was more aligned with what I believed in, and it continued to open doors. I think it’s also what brought me to explore beyond everyday life and look for a more esoteric meaning of life. It goes together… It’s magic in a kind of way, but it’s not, so then you’re curious, what’s the mechanism, what’s going, what are we? Because people who just follow the medicine and suppress everything don’t realize what’s happening in their body. You take a little pill that’s not supposed to be anything, its placebo, and yet to feel like a million bucks. It changes you. ❦

Further explorations:

Jacqueline’s regenerative farm, Testbed

Alec Zeck’s interview with homeopath Melissa Kupsch (RMDY Academy)

The Science of Homeopathy by George Vithoulkas